You call it dictatorship, I call it efficiency

Utopian cities of the world. Part 3: Stories of Astana, Singapore, and Seoul

Hello from New York,

This is a continuation of my mini “series” on Utopian Cities of the World.

I’ll begin with: Asian cities’ success is defined by effective central rule. You can call it authoritarian dictatorship. I call it execution efficiency.

Large-scale infrastructure development projects that take the West generations to achieve take just decades in Asian cities. Example: NY took ~37 years to build 1.8 miles of subway, while Beijing built 342 miles over the same time period.1

And to me, every year I visit my hometown Beijing, I see change: a new shopping district pops out of nowhere, a new riverfront poised to be the city’s own Venice. Whereas every time I come back to America, things remain the same.

Today, I want to tell the stories of three Asian cities: Astana, Singapore, and Seoul, inspired by a book I read recently: “Asian Cities: Planning and Development” 亚洲城市的规划与发展).2

These three cities share a similar kind of central control and policy-making, top-down masterplanning, and a beautiful vision for building cities of the future.

01 Astana, Kazakhstan

Following Kazakhstan’s independence in 1991 came a bold move by President Nursultan Nazarbayev: moving the capital from the largest economic center of Almaty to an underdeveloped town of Astana.

The vision was to build it into a smart, sustainable city and to grow the population from 250,000 to 1 million by 2030.3

The move to Astana (at the time called Akmola) was geographically strategic. Almaty was surrounded by the Ile-Alatau mountain range and thus, its growth potential is limited along with seismic risks. Astana, on the other hand, is positioned in the center of the country on the major transport node for the distribution of resources plus limitless capacity for expansion.

He hired Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa 黑川纪章 to masterplan the capital. Kisho’s proposal arose from the competition, aligning with the government’s development ideals. Astana valued a “symbiosis” of history and the future, developing the historical north and the new administrative center south of the Yesil (Ishim) River at the same time.

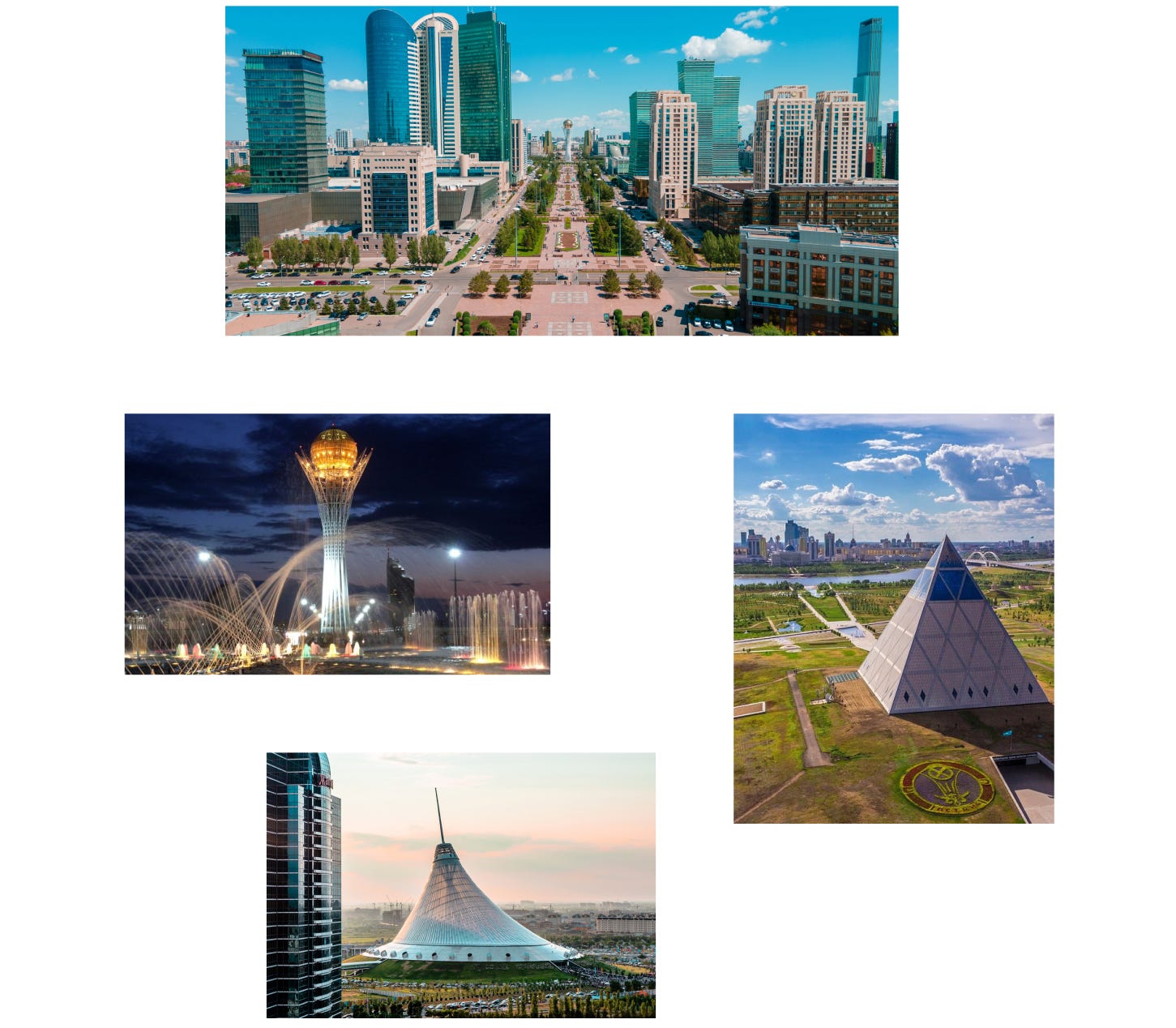

In just twenty years, numerous architectural landmarks were built that embody the traditional and modern, many on a central east-west axis along Nurzhol Boulevard.

Top: Nurzhol Boulevard (source: The Astana Times)

Left: Bayterek tower, a national monument that symbolizes a respect for its historic roots along with wishes for the future (image source)

Right: Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, a glass pyramid by Norman Foster built for the Second Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religion (image source)

Bottom: Khan Shatyr shopping center, structure inspired by the tent of the nomadic people (image source)

A green belt of “one million trees” around the city perimeter was designed (and actually planted with 9.6 million trees) in response to the region’s -30°C winters and +30°C summers. It serves as an ecological buffer to help moderate the microclimate and reduce dust storms.

The progress of Astana, I believe, can be attributed to the execution of a central vision from President Nursultan.

In the US, federal, state, county, and private landowners all have competing interests, along with the perpetual battle on whether the budget comes from the federal, state, or the municipality (side note, MTA, the transit authority managing NYC subways, is owned by the State of New York and not the city, and is why our subways do not get build4). Thus, such large-scale projects would remain on the drawing board for decades.

A green belt of over 100,000 hectares (1,000 km²) was built – larger than all 5 boroughs of New York City combined: 778 km² (source) (image source), as indicated on the Google map satellite view. A successful large-scale afforestation project (photo source: Astana Ormany LLP)

“Astana’s is a story of grand vision meeting revenue. The vision was that of Kazakhstan’s veteran president Nursultan Nazarbayev, in power since 1989. The revenues come from oil, gas and other natural resources.” (Forbes)

Kazakhstan utilized some of its oil revenue to build new infrastructure for the capital. This hinged on leveraging centralized power to fast-track decisions and bypass land disputes common in more democratic processes.5

I think a metric for measuring the success of a city (amongst other ones such as GDP, income per capita, livability, and happiness score) is population: the notion of voting with one’s foot. By this metric, Astana grew from a population of less than 250,000 to 1.3 million today, exceeding the original 2030 target 7 years ahead of schedule.

And by the way, note the patterns in the relocation of capitals: Brazil moved its capital from the coastal commercial center of Rio to Brasilia, Nigeria from the financial capital of Lagos to Abuja.

Brasilia, Abuja, and Astana all had the same utopian vision. But beautiful visions without execution efficiency become partial failures.

Today, the cities in Brazil and Nigeria I chose to visit first were Rio and Lagos. For Kazakhstan, I’d pick Astana.

02 Singapore

Speaking of one man’s vision, Singapore is a paramount case study to learn from. Singapore’s success can be attributed to one individual: Lee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister of Singapore from 1959 to 1990. In this case, long-term leadership ensured political and policy continuity to execute multi-decade visions.

His wanted to transform Singapore into a first-world metropolis through pragmatic governance, social cohesion via multiracialism, and ruthless efficiency.

Singapore is 715 km² (5 boroughs of New York City are 778 km²), 133 km² of which came from reclaimed land.

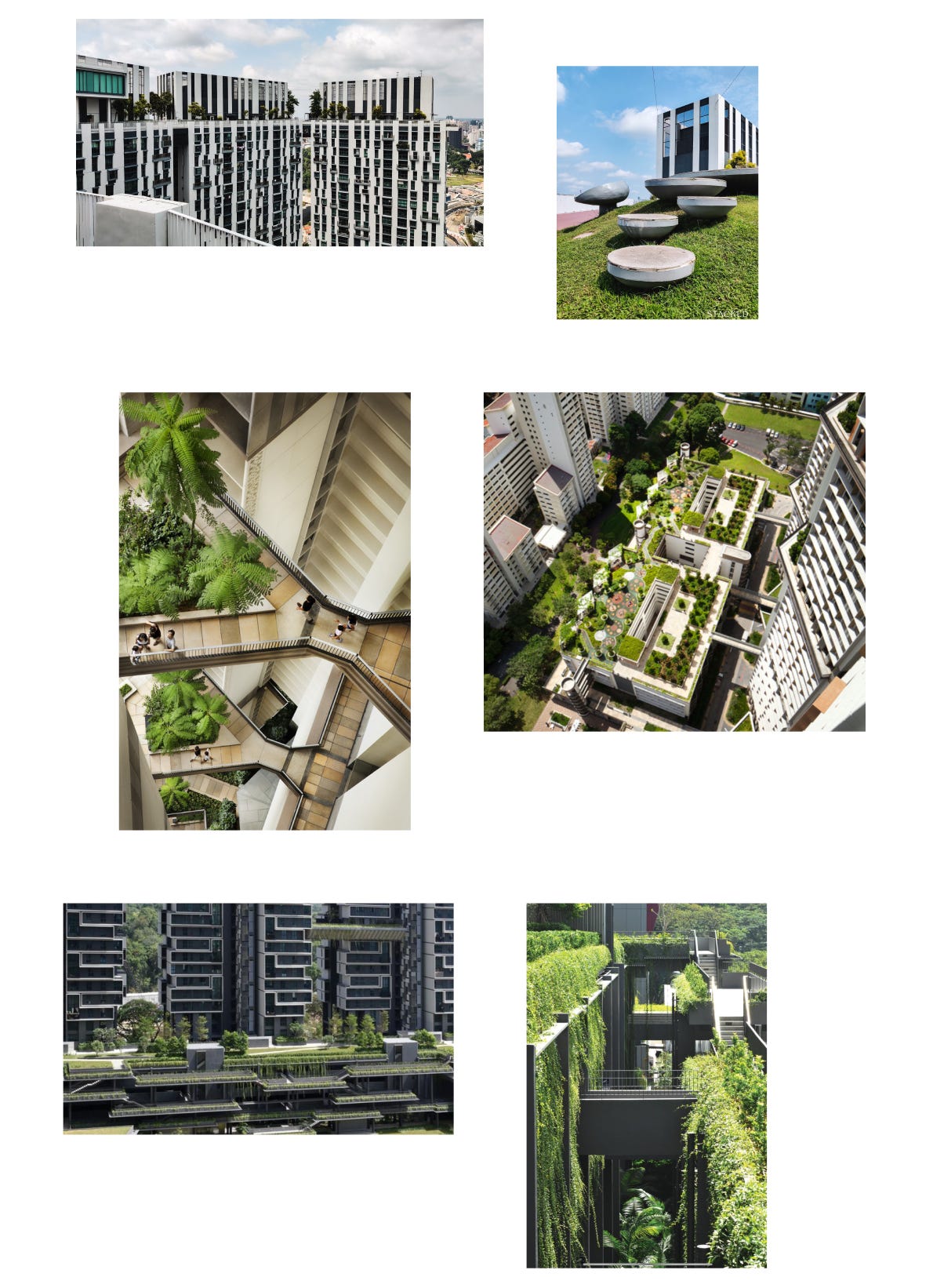

Singapore is an island, and like Manhattan, it cannot sprawl. Thus, the country was designed and built with this constraint in mind. The intention was to build upwards at the outset 高层高密度, integrating high-density urban living with abundant greenery and human-centric spaces.

This design philosophy resulted in the quintessential Singapore look—vertical greenery, rooftop gardens, and vegetation exploding along building facades.

High-rise development for space efficiency, mixed-use buildings, and extensive greenery integration.

Examples of HDB Public Housing in Singapore:

Top row: The Pinnacle@Duxton (2009) by ARC Studio Architecture + Urbanism and RSP Architects Planners and Engineers (image source)

Middle row: SkyVille @ Dawson (2015) by WOHA Architect (image source)

Bottom row: SkyTerrace @ Dawson (2015) by SCDA Architects (image source)

To tackle the issues around affordable housing, the Housing Development Board (HDB) was established in 1960, along with Land Acquisition Acts.

Between 1959 and 1984, the government acquired a total of 43,713 acres of land, which constituted about one-third of the total land area of Singapore at the time. Today, more than 90% of the land is owned by the state.6

HDB then purchases land from the government to build.

To create affordable housing at scale is not about requiring 20-30% affordable units in a handful of rezoned neighborhoods.7 It is about creating 120,000 flats that give housing to 34.6% of the population in 10 years—reducing monthly payments to just 15% of family income (compared to NYC’s renters paying 30-50% in rent).

The beautiful buildings shown in the above photos are Singapore’s version of “projects”. “Projects” 组屋 in Singapore are a safe and comfortable dwelling for the middle-class. In contrast, in America, “projects” are stigmatized.

By controlling 90% of the land, the state made “projects” the only housing option for everyone, not just the poor.

Today, about 80% of Singaporeans live in “projects”. In contrast, in New York, just 9% live in affordable public housing.

ArchDaily: “Corridors of Diversity”

The housing agencies also developed some rather creative policies. One required different ethnic groups to live under one roof in strict ratios. And the policy seemed effective: cultural integration is apparent not only in residential communities, but at work and in education. Another dictated that priority goes to married couples if the housing they choose is close to their parents (Married Child Priority Scheme 2002), so grandchildren can live near grandparents as a way to encourage multi-generational housing. I grew up in Beijing in a household of eight along with my aunt, cousin, and grandparents, and I can argue that such multi-generational living is the best arrangement.

Ultimately, the people of Singapore have a deep sense of trust in their government.

“I had seen how voters in capital cities always tended to vote against the government of the day and was determined that our householders should become homeowners, otherwise we would not have political stability.” —Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965-2000

Since his first policy on housing reform, Lee Kuan Yew saw a connection between homeownership (~90% of Singaporeans are homeowners through 99-year leases), political stability, and national identity. By giving citizens a material stake in the nation’s success via homeownership, public housing was elevated to the level of strengthening citizens’ confidence in the government.

And Singapore, at this moment in time, is the only country in the world that has transitioned from Third World to First in one generation.

03 Seoul, South Korea

Seoul, the capital of South Korea, is a city with a history of over 600 years. Yet the metropolitan we know today was built in just thirty years from the 1960s to 1990s—known as an “era of quantitative growth” 量化成长时代, where progress was measured purely by numbers and economic growth.

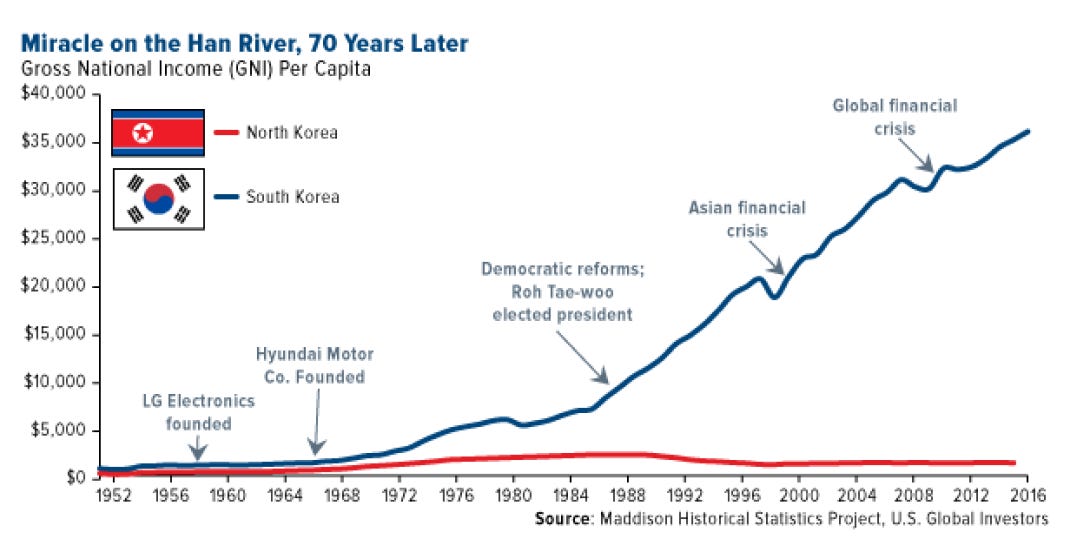

North and South Korea started with similar Gross National Income per Capita following the Korean War (1950-53). There is a difference between authoritarian and totalitarian leadership. The former propelled South Korea into a period of post-war construction known as “Miracle on the Han River.”

President Park Chung-hee established legal frameworks that enabled rapid urban development, including the Urban Planning Law, Land Acquisition and Readjustment Acts (1962).

The government implemented a comprehensive management and development 综合治理和开发 of the the Han River (graph source: Wikipedia).

To encourage expansion of the city south of the Han River, the government deliberately made planning codes strict in the north, making renovation and expansion difficult. Businesses had to move to the south. This kind of forced northern stagnation is possible under centralized rule.

And this was the origins of Gangnam 江南 (“Gangnam” means river south), popularized by PSY’s Gangnam Style.

“Government-led rapid growth and development sparked national and citizen pride.”— Kim Donyun 金度年, professor at Sungkyunkwan University

In addition, the expansion was enabled by the Land Readjustment Program, where the government acquires the land and installs infrastructure (e.g. roads, public facilities), increases the value of the land, and redistributes smaller but more valuable serviced plots back to owners (in other words forcing developers to buy back land they didn’t want). The program pays for itself.8

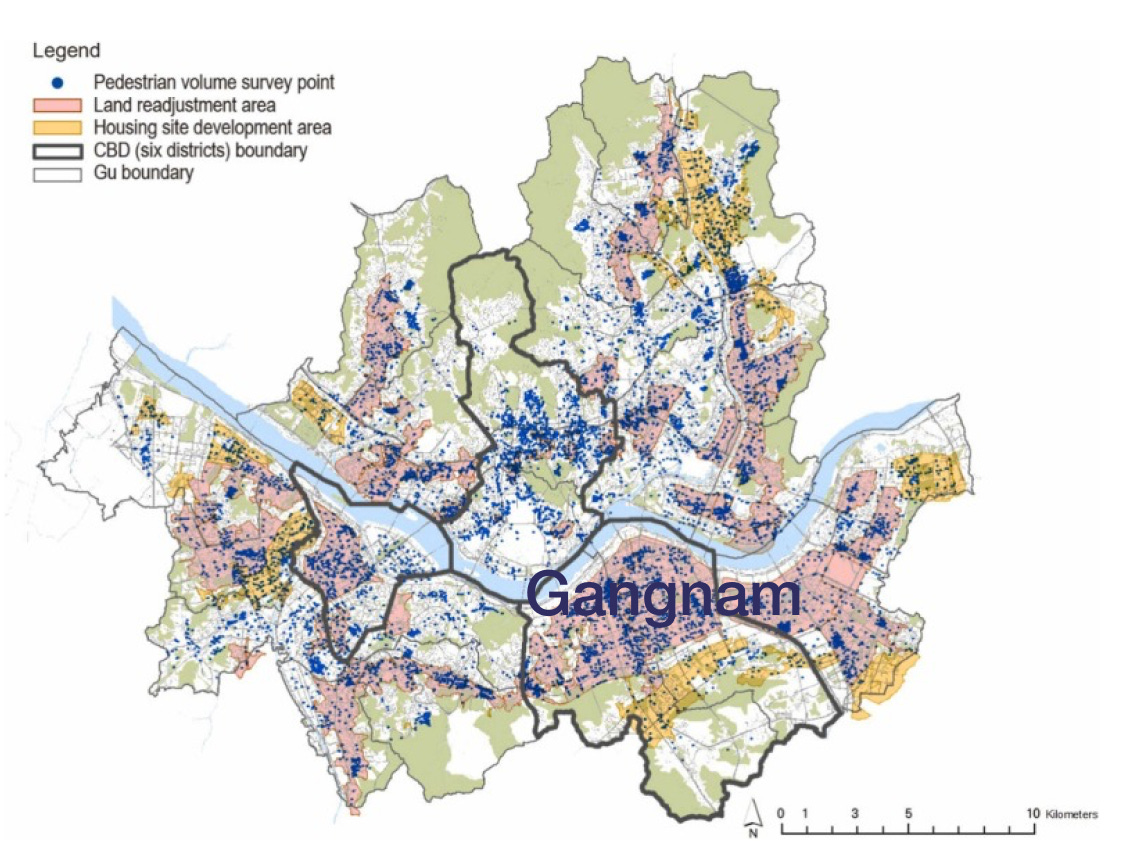

Land readjustment area is highlighted in pink (image source). As Gangnam transformed from farmland to urban land, land value increased ~13,000 times over 26 years (Land Value-Infrastructure Nexus in Land Readjustment: A Case Study of Yeongdong (Gangnam) in Seoul, South Korea).

The central planning is not without trial and error.

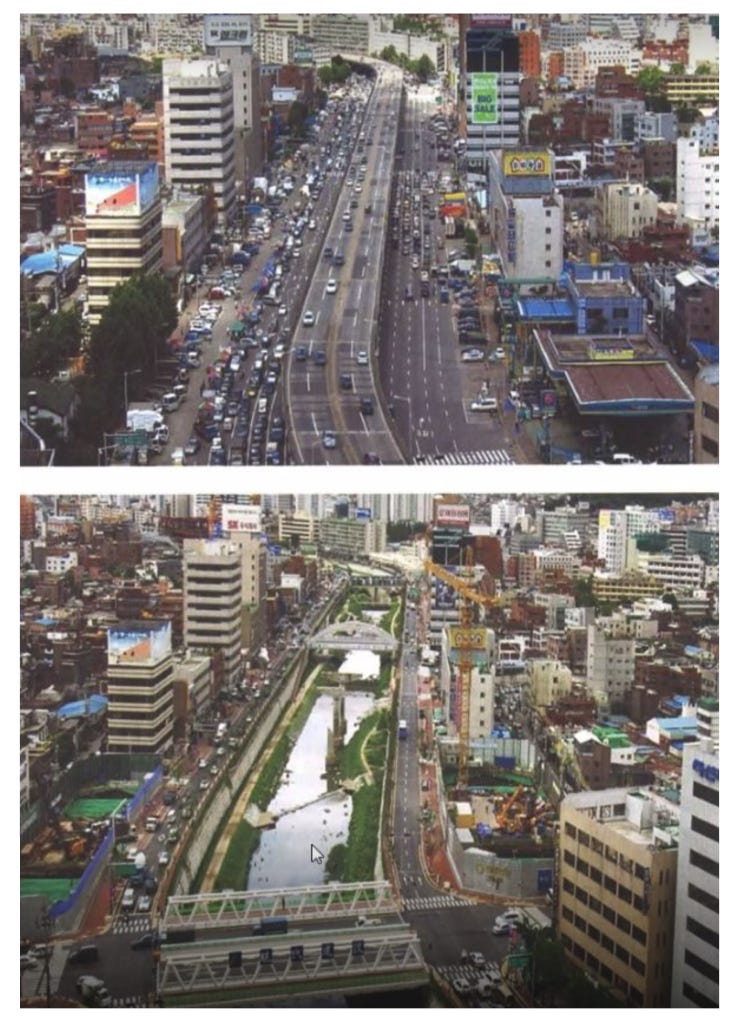

During the era of quantitative growth, the government focused solely on speed and infrastructure buildout and adopted easy-to-implement band-aid solutions, such as burying the polluted Cheonggyecheon River and building an elevated freeway on top of it.

At the turn of the century came a realization: the need to focus on cultural value, sustainability, and urban livability, to focus on the “software” elements of the city. In a bold move, Seoul demolished the highway in the city center that once buried the Cheonggyecheon River. The river was restored and public space was built to spark cultural activities in the region.

If this had been in San Francisco, a single vote from a household next to the highway would’ve halted this entire project.

Transformation of Cheonggyecheon 清溪川 复原项目 from an elevated freeway (2002) to an urban greenway (2003). Photos by Na young wan, Seoul Metropolitan Government.

South Korea became more democratic in 1987, creating single, non-renewable 5 year presidential terms. Though, the planning frameworks from earlier persisted and master planning continued, however with democratic modifications such as public negotiations. The Miracle continued.

The story of Seoul is one of continuous reflection and self-examination: the courage to admit the mistakes from earlier planning, the speed and efficiency in demolishing existing infrastructure, and the ability to allocate the resources to build new ones.

—

A core sentiment that unites these Asian cities is a trust in the central government.

Whether long-term leadership screams authoritarian, or a means of political continuity that enable multi-decade projects, is perspectives.

When the government forced relocations for the Astana city center, the housing projects of Singapore, the Gangnam development, and the Cheonggyecheon restoration, people accepted: “The government has my best interest and my city’s best interest in mind, I can move.” It may have bypassed democratic processes, forcing community displacement and sometimes demolishing heritage, the result is green public space, affordable housing, life between buildings, and arguably, a better city.

Whereas, in Western individualism, the narrative becomes “I have the right to this home. The government cannot force me to move.”

There isn’t a right or wrong. Neither is inherently superior. It boils down to the spirit of the people.

One who is community-oriented believes in accumulating resources for the greater collective good; one with individualistic ideals will lead grassroots change in their own way. One prefers centralized ruling; another prefers decentralization of power. Some are happy entrusting their well-being to the government; others prefer to take part in the choice.

Centralized power can catalyze urban transformation, only when it’s aligned with the cultural values of the people.

Lastly, there is a need for continuous re-examination. Such as the case with South Korea, the people became more democratic and that altered the structure of the government. Whether this democratic structure will continue to shape the urban fabric the way it did is unknown. Whether people will become more democratic with globalization is unknown.

What the government needs is to respond to the people and help them in ways they want to be helped.

To be continued.

If anyone has any commentary on the realities of the cities on the ground, it would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you friends from Write of Passage and Essay Club for the feedback and edits: Matthew Beebe, CansaFis, Ri, Michael Dean, and Patrick O’Loughlin.

From 1980 to 2017. NY: Transit Costs Project Final Report, Beijing: Wikipedia, plus Saumya ’s Why does it take so long and so much for our government to build today?

An Asian Cities Forum was held in Shanghai annually from 2013-2016 (as a continuation of the discussion from the Shanghai Expo 2010) where urban planners and government officials from Asian countries such as Singapore, Korea, and Indonesia, along with those from Central Asia and the Middle East such as Kazakasthan, Sri Lanka, and the UAE gathered and shared knowledge on city planning, management structure, and policy implementation. Some of the insights from these discussions are accumulated in this book, published in Chinese in 2018 (and not yet translated into English).

(image source: Tongji University)

“Creating the Metropolis: Observation of New York’s Space and Institutions”《创造大都会:纽约空间与制度观察》by Luo Yuxiang 罗雨翔

A 1995 Presidential Decree created a “seizure for state needs” mechanism,” leading to massive allotment of land for construction in the city center. While the decree “allowed private ownership”, the “seizure for state needs” concept was widely interpreted. The Significance Of The Land Issue Has Not Yet Been Realized By The Authorities Of Kazakhstan

Inclusionary Housing Program: Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH)

great read!!! and thanks for the shout :)))

As a Singaporean, I find it very fascinating when people describe Singapore this way. What you wrote is 100% factual, but there are nuances that make reality less rosy. It's impossible to get to in the short span of a comment, but in short the projects that you speak of are somewhat of a lottery system. If you get a unit, it's great because you buy it cheap and sell it in the open market. Many people build wealth that way. And if you do not, you lose out on this wealth-building opportunity that everyone else has.

And to the question of whether Singaporeans trust the government... we have been ruled by 1 party since independence. We had an interesting election this year. I think this article sums it up: https://www.ricemedia.co/did-we-hope-for-too-much/