My favorite, untranslatable words: English vs Chinese

Value systems from the east and the west

Hello from Beijing,

I make an effort to spend two months in China every year. In doing so, I continue to solidify and maintain my value system.

Over time, I’ve made a collection of my favorite words in English and Chinese—sentiments, rather—that do not exist in the other language. My values, I realize, cannot be defined in a single language alone. They stem from rooted cultural values and serve as my compass as I navigate the world.

agency /ˈeɪdʒənsi/

Agency is a word that can only exist in the consciousness of a highly individualistic society.

It requires strong will, a sense of self, and the belief that we as individuals can drive change in our lives. Those with agency are the type I admire and constantly remind myself to become.

A closeish translation in Chinese is 自主权 (zìzhǔquán), meaning autonomy and the right to choose, but this sentiment seems to come from the outside—one that is granted upon us, perhaps as a result of the political environment. Agency stems from within.

In China, we rely on the family and the government. Once, while sitting in traffic in Xiamen because many taxi drivers were crowding the gate1, I remember my taxi driver saying, “这政府都不管吗?(“Is the government not going to do anything about this?”). In a Western society, instead of relying on the government or municipality, the instinct is to resolve it on our own or to drive the change we want to see.

Agency means changing careers rather than staying in an unfulfilling job, having difficult conversations to better a relationship, and flying to Brazil during COVID rather than giving in to the default option of staying at home.

眼神 yǎnshén

The direct translation of this word is “eye behavior” or “eye expression.” It means that the eyes carry emotions and represent our internal state. The eyes speak, perhaps louder than words.

The closest English translation is “eye contact.” But here, there is actually no direct “contact”—it’s a subtle sense of communication and psychological connection. In the Western language, communication is more obvious and direct. While in the Eastern world, it is a bit more subtle and happens in the unsaid.

Once I was at a relational workshop in China. Five volunteers were asked to form a circle facing each other as a fictional family. In a few moments, they looked deeply into each others’ eyes. The key was that in this mock practice, they didn’t speak or ask questions—they only felt. They followed their emotions and acted from the heart. It’s like improv but without words.

I had a chance to chat with the “dad” from the family afterwards. He said, “From the first few seconds when we stood in the circle looking into each other’s eyes, I could already predict how the others would behave.”

I recalled moments where I could have hurt someone without realizing it, from yǎnshén alone. Often, I focus a lot on the words but sometimes, more can be felt.

yǎn means eye, shén is a kind of facial communication2 (it’s also the same character as God). Behind the eyes there is meaning, there is purpose, a shine, a story. It is as if there is a little spirit in those pupils.

unapologetic /ˌʌnəˌpɒləˈdʒetɪk/

I dug through my gratitude diary. In a sea of Chinese, I spotted an English word “unapologetically做自己”—to be ourselves unapologetically.

In Chinese, the translation is 不道歉的 (bù dàoqiàn de) “not apologizing” or 毫不愧疚 (háo bù kuìjiù) “without any guilt.” Neither capture the weight of that defiant self-acceptance.

Being unapologetic means we can be our truest selves without feeling we owe anything to the world or to one another, to stand by our beliefs without the need to soften them for others’ comfort. It comes from a place of authenticity and strength. It is a freeing feeling, made possible from a culture that values freedom and self-assertion.

When I talked to my grandma about my dating experiences, she advised, “maybe you shouldn’t tell your future partner about all of these (and they’re not crazy).” Whereas to me, shouldn’t a partner accept me for all that I am?

“Sorry but not sorry.” It’s not that we don’t care about others, in fact, the utmost form of care comes from a place where we are most honest with ourselves.

合适 héshì

In the context of deciding on the right partner, in Chinese we seek the “suitable” or the “fitting.”

But there is a strong difference in the feeling the term evokes. In the English translation, it feels passive, like the result of an arranged marriage where love is deemphasized: “we could have chosen better, yet we settled for someone suitable.”

In the mind of the Chinese, however, héshì is a powerful feeling of contentment in a relationship where we’ve made the right choice. It comes from the fact that our lifestyles are compatible, what we want in our lives matches, and our families and friends know each other 知根知底. It embodies it all and it’s so much more than love.

Instead of asking, “Do you like him?” we ask, “Do you think he’s héshì?” It means we’re good for each other, and it’s the strongest foundation to lifelong love and support.

grounding /ˈɡraʊndɪŋ/

I love the feeling of being grounded. It is a sense of inner alignment with our values and confidence in making choices that represent our truest selves.

In Chinese, a close translation is 踏实 (tāshi) or 安逸 (ānyì), meaning a peaceful contentment or comfort. It’s this calm feeling of having found our place in the world.

But grounding is different. It is an active force backed by present-moment awareness as a result of emotional regulation. The Western therapeutic tradition assumes individual responsibility in taking control of one’s mental state, active management of feelings, and a mechanical reset to a personal center.

Linguistically, “to ground” is a verb, an active pursuit, while tāshi or ānyì describe a state of being and cannot be made into a verb. In Chinese, it’s not so much that the feeling of centeredness and ease doesn’t exist, it’s the idea that it is an active process, intervention, plus a bit of agency.

”Tomorrow, Integral Grounding dialogue session at Karma House Tattoo. All welcome.” I saw this piece of advertisement in a mindfulness WhatsApp group.

These are practices where we leverage another’s aptitude at emotional regulation for our own. With these learnings, I feel firmly rooted to the ground.

老天 lǎotiān

Lastly, lǎotiān. It’s my version of God.

In a literal sense, it means “old sky.” To me, it is the all-encompassing being that lives in the sky and in our hearts. One entrusts their prayers to 老天爷 lǎotiānyé (“Old heavenly master”) and utters “老天有眼啊,谢天谢地” (“You have eyes. Please see us. We thank the Sky and the Earth.”) It’s a feeling of relief and gratitude because divine justice has intervened.

It is not so much a religious concept, but spiritually surrendering to something greater than us. I grew up without a religion or God, yet lǎotiān is “someone” I secretly talk to. Every time I feel a sense of despair, I look up to the sky and find a bit of comfort. It doesn’t carry any formality. It’s my secret faith.

—

It’s less a translation of words than a translation of entire mental frameworks.

The Western world teaches me to be authentic to our own experiences and to find strength in the self, while the Eastern world teaches me to notice the details in others’ emotions, to find support and to trust my spirit to the divine.

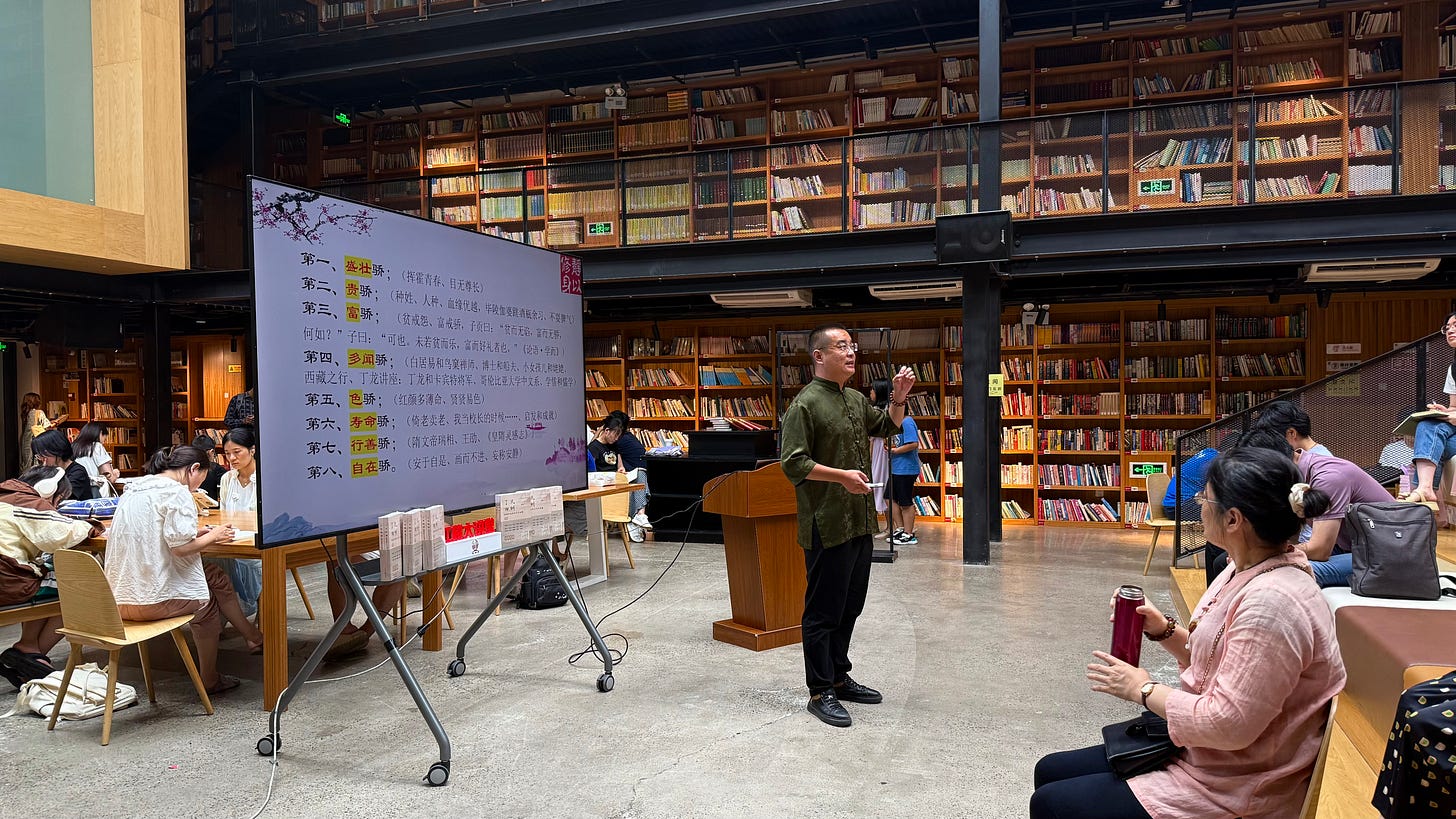

Sitting at the 红楼藏书阁 (Red Chamber Library)—a local library not far from home, I stumbled upon a talk on seven types of ego and humility, feeling grateful as these abstract concepts and ideas continue to shape my worldview.

Thank you friends from Write of Passage and Essay Club for the feedback and edits: Rik van den Berge, Mak Rahman, and Michael Dean.

Taxi, known as 黑车, are scam taxis who charge exceedingly high prices (ie 4x the actual fare) at crowded locations. They often refuse passengers who are unwilling to pay this fare, and wait at the gate for the eventual one that would.

shén also means 神情 shénqíng, or mien—inner thoughts and feelings expressed through facial expressions.

哈哈,There is no word like “缘分” word in English.

眼神 seems like it might translate to “the look in one’s eyes” rather than “eye contact.” I feel that while English doesn’t have a succinct word to capture a general concept of eye emotions, there’s lots of ways to explain specific emotions being conveyed via the eyes, like a cold stare, loving gaze, timid glance, etc. English also has expressions such as “eyes are the windows to the soul.”

This was a fun read! I’d read more content like this